Longy Cemetery

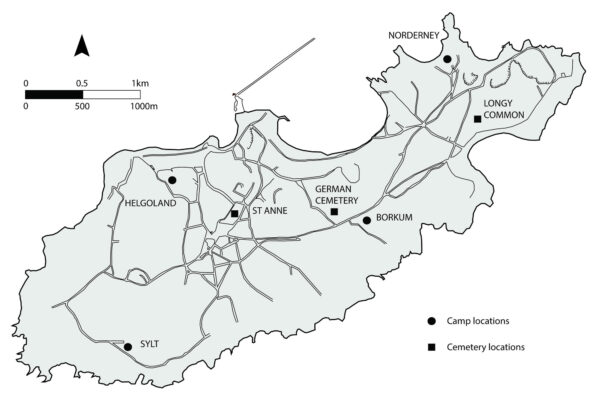

- Country: Alderney, The Channel Islands

- GPS: 49° 43' 23.0988 N, -2° 10' 31.08 W,

- Address: Longy Common, off Route des Carriéres

- Operational: N/A - Active

By Caroline Sturdy Colls and Kevin Colls

After the death of a forced or slave labourer was registered, in theory a system was in place whereby ambulance drivers and a one-eyed gravedigger would collect their corpse for burial.1 A cross bearing the name, date of birth and date of death of the deceased was then supposed to be inscribed and erected immediately in one of the island’s official cemeteries. The first of these was an existing cemetery in St Anne, which had been used to bury the island’s population for centuries. The second location was a purpose-built cemetery, known colloquially as the ‘Russian’ cemetery, referring to the fact that it was predominantly Soviet workers who were buried there.2 This cemetery was located on Longy Common (sometimes spelt Longis) in an area of scrubland on Alderney’s south coast, overlooking Raz Island Fort.

Taken on face value, photographs of the cemeteries and burial records created by the Germans seem to suggest that an ordered burial system was in place which took place within these neat cemeteries. Further analysis of witness testimony, documents, photographs and the results of the exhumations carried out by the VDK in 1961 coupled with archaeological investigations, suggest that the reality of the burial “system” was quite different than the official procedures suggest. Witness testimonies suggest that, in these cases, the certification of death and burial of bodies was not carried out swiftly, if indeed at all. Secondly, when burials of OT and SS labourers did take place, there was also considerable variation in terms of how bodies were interred, influenced by where and when individuals died, who they were, and internal and external pressures placed upon the German administration.

Most labourers who died on Alderney were reportedly buried within the cemetery on Longy Common.

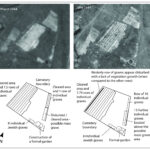

The evolution of the cemetery

An image taken on the 30 September 1942, shows no obvious burial sites on Longy Common, even though nine people were supposed to have been buried there by this time.3 By 23 January 1943, graves were present across five rows.4 A small cluster of graves in the north-east corner of the area appear to have been in situ long enough for vegetation to have grown on top of them, suggesting that they may have been dug first. At this time, the cemetery did not have clear boundaries, but the graves appear to have been confined to the north-west of what would later become its fenced area. Tracks can clearly be seen, revealing the routes taken to transport the bodies to the graves and a small upstanding structure appears to have existed close to where these converged. By August 1943, a boundary had been constructed, consisting of a raised earth embankment upon which fence posts were placed.5 At this time, seven and a quarter row of graves were present. Vegetation growth patterns also provide a good indication of the graves that were recently dug (at the south-east end) compared to those that had been in existence for some time (at the north-west end). Sometime prior to August 1943, a circular feature was created in the south-east corner of the cemetery, adjacent to the entrance. This has been interpreted as an ornamental garden.6

By 1944, it seems that the enthusiasm for maintaining order. German reports offer evidence for this. Following a visit to inspect the graves in 1944, Sonderführer Hans Spann recalled: ‘I was struck by the disorder [of the cemetery] and marked lack of dignity with which the corpses had been buried…I am extremely doubtful if the names on the individual graves were correct’.7 Obergerfreiter Kraus recorded how staff were ordered ‘to level a number of graves on the Russian cemetery remarking, the cemetery was too big. He ordered, too, that a cartload of crosses with names on them were brought to the farm from the cemetery and burnt there in the kitchen’, following the invasion of France by the British in 1944.8

A British intelligence map created in 1945 from aerial photographs from 1944 and 1945 also denotes Longy Common cemetery and states that the graves were unmarked at this time.9 Yet, by the time British investigators arrived to record the site, some of the markers had been reinstated. Almost certainly, they did not correctly indicate who was buried in each individual grave. The investigators noted that the main area consisted of seven rows containing 255 marked graves whilst the bodies of eight Jews were buried separately on the south side of the cemetery.

When exhumations took place in 1949 and 1961, the bodies of 329 individuals were found buried in the cemetery, 73 more than the number of markers suggested were present.10 Identification of these individuals was not possible in the absence of records. The explanation for this higher number of interments is two-fold: (1) two bodies were found in some of the graves and (2) unmarked burials existed within the cemetery, in part as a result of the continuous marking, unmarking and re-marking already described.

Rumours about more than one body being buried in the graves had already circulated amongst those who had been held on Alderney during the occupation long before the exhumations took place. Some labourers even claimed to have witnessed such occurrences.11 Cyprian Lipinski, a Polish OT forced labourer, reported that:

‘the bodies were buried sometimes naked, sometimes clothed. At the end of 1942 I saw one such “burial” from the immediate vicinity. I saw how two corpses were put into one grave. First one was thrown in and his body was covered with sand (this was done by kicking) then the second body was thrown into the same grave. Once more I affirm with certainty that on this occasion I saw two bodies put into the same grave.’12

Mass Grave

British investigators actually documented what they believed to be a mass grave within the cemetery in 1945.13 Significantly, the grave was alluded to in a report prepared by the IWGC on the 25 June 1945 and in one of Pantcheff’s previously classified Periodical Reports on Atrocities Committed in Alderney, yet it has never been referred to as a mass grave in any subsequent publications, including those by the latter author himself.14 A survey in 1952 by Watson, a representative for the IWGC, and subsequent correspondence regarding his report provide the greatest insight into the nature of this potential grave.15 Other independent reports, such one from the South West Regional Inspector for the IWGC, also allude to the grave: ‘you refer to a large common grave which I take to be a communal or trench grave on the east side of the Cemetery, in which 43 Unknown Russians were buried. Our record of this grave is that it was roughly level turfed and about 40 yards long’.16

A series of modifications were made to the cemetery following Watson’s survey which may account in part for the lack of knowledge of the mass grave’s existence and explains why some further individual graves were also found. Following consultation with the Garrison Engineer, Watson did recommend the erection of a bronze plaque in the centre of the mass grave, which would display the words ‘in memory of 43 unknown Russian citizens, who died during the German Occupation 1941-45’ and its outline was to be marked with concrete posts.17 However, problems with funding and liaising with the Soviet government, coupled with unsatisfactory work at the site, meant that progress erecting the memorial was slow.8 A graves registration form created by the IWGC in 1958 states of the mass grave that the ‘outline of this grave is marked by 6 concrete markers and a bronze plaque has been fixed to a concrete block in the centre of the grave’, thus suggesting that some of the work was finally undertaken.19 A plaque bearing the exact text that was present on the original British monument (but with the number 43 scratched out) now resides in the Alderney Museum, though its provenance is not given.

Analysis of aerial imagery and geophysical survey (using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and resistance survey) provide further insights into the nature of this area. High resolution imagery taken in and after August 1943 demonstrates that the ground had been disturbed in the area that would later be marked as a mass grave, although unfortunately the lack of aerial images between January and July 1943 makes it impossible to pinpoint the exact date that excavations began in this area.20

The GPR survey confirmed the presence of a linear feature measuring approximately 21m by 4m (but likely extending outside the survey area to the south).21 It was located in the same area and on the same alignment as the mass grave feature identified in the aforementioned aerial photographs. This feature is first clearly visible at a depth of 0.7m below the surface and likely extends to circa 1.3m. Resistance survey undertaken at the site and the GPR results demonstrate several smaller anomalies and areas of disturbance exist in the upper layers (0m to 0.7m).22

Exhumations

As mentioned above, when exhumations took place in 1949 and 1961, the bodies of 329 individuals were found buried in the cemetery, 73 more than the number of markers suggested were present.2 Looking at the methodology used by the exhumation team in 1961 in general, it is evident that the body recovery process was not thorough and that it certainly did not meet the standards that would be expected during exhumations today. Firstly, no report detailing the actual excavation procedures is available, making it difficult to know exactly what the investigators found.24 Secondary sources indicate that the exhumations were undertaken hastily and only basic information about them noted down. The VDK did not employ professional body recovery specialists nor scientists and local volunteers also appear to have been used to help with the exhumations.25 A report written by the Officer of Health (based on sites throughout the UK) was less than complimentary of the VDK’s exhumation procedures elsewhere: ‘the bones were hacked out with small hand tool, any soft parts scrapped off and the bones put in a plastic container. The discarded remains and the coffin were thus left in the grave’.26 Unfortunately, the exhumation report created by the VDK in 1961 does not include specific details about whether any part of the possible mass grave was excavated in full or how any bodies found were configured.

After these exhumations took place, it was assumed that all the burials on Alderney had been found and no further searches were carried out until archaeological investigations led by the authors took place from 2010-2017. Given the paucity of documentation regarding the ways in which the Longy Common cemetery was searched and the ways in which the bodies were removed from the graves, it seems unlikely that (a) all of the bodies that existed in the cemetery from the occupation period were found and (b) that all of the remains within each grave were adequately recovered. In the absence of forensic archaeological search and recovery methods at this time, it is highly likely that considerable evidence concerning the nature of the burials and the condition of the remains within them was lost. Certainly, no known documents exist that outline the size of the graves, their depth or their form, nor do any that suggest that analysis of the remains themselves was undertaken, for example, to establish cause and manner of death. It also appears that the team only focused on specific areas within the cemeteries; thus, their work was a recovery exercise as opposed to a thorough search for all the graves and human remains that might have existed.

Outside the cemetery

Historical research and the archaeological works also indicated the possible presence of further burials outside the cemetery boundaries, providing further evidence of the deceptive nature of the burial procedures employed by the Germans. Aerial photographs taken on 12 August and 3 October 1943 reveal a trapezoidal area of ground disturbance to the north of the marked cemetery measuring a maximum of 31m by 27m.27 Ongoing disturbance is evident in images taken in March 1944.28 Within the GPR results for this area, a rectilinear feature measuring approximately 14m by 9m is visible at a depth of between c.10cm and c.1.5m.29 It exists on a north-east – south-west alignment. The northern cemetery boundary runs across its southern end, which implies that either (a) this feature was dug and backfilled prior to the boundary’s creation (sometime between the end of January and the middle of August 1943) or (b) it was dug after the removal of the boundary in the 1960s. However, based on the correlation between the location of this feature and the disturbance visible in the aerial photographs, it seems more likely that it dates to the occupation period and could represent an area of further burials.

Further evidence for this is provided by a witness testimony alluded to in a newspaper report written by a correspondent who accompanied the British liberating forces on 16 May 1945. A Mr Pike, who had lived on the island throughout the occupation, showed the journalist an area where he believed additional graves had been ‘ploughed over’ ‘higher up the slope’ than the main Longy Common cemetery e.g., to the north, towards Norderney camp.30 Hence, it is possible that he was referring to this same area.

In the absence of excavation, confirming whether any bodies do reside in these areas is impossible. However, the fact that these features appear so close to the cemetery at a time when the Germans were under mounting pressure to give the appearance of an ordered cemetery adds some credence to the theory that they could be additional graves. Any attempt to establish the number of bodies that might be present within these areas would also be purely speculative in the absence of excavation, but it should be noted that their combined area closely matches the size of the area of the cemetery that formerly contained the marked burials. Currently, Longy Common cemetery is not marked, and it remains under threat from future development works, natural erosion and animal activity.

References:

1 M. Bunting, The Model Occupation – The Channel Islands under German Rule 1940-1945 (London: Harper Collins, 1995); T. Freeman-Keel, From Auschwitz to Alderney and Beyond (Malvern: Seek Publishing, 1995); S. Steckoll, The Alderney Death Camp (London: Granada, 1982); J. Dalmau, Slave Worker in the Channel Islands

2 For a discussion about the arbitrary use of the term Russian on Alderney, see Chapters 1 and 11.

3 NCAP, ACIU MF C1090, 30 September 1942.

4 NCAP, ACIU MF C1183, 23 January 1943; NCAP, ACIU MF C1188, 26 January 1943.

5 NCAP, ACIU MF C1563, 3 October 1943.

6 C. Sturdy Colls and K. Colls, Adolf Island: The Nazi Occupation of Alderney, (Manchester University Press: 2022)

7 TNA, WO311/13, ‘Statement by Mil.Verw. O/Insp. Hans Spann’, 5 September 1945.

8 TNA, WO311/12, ‘Statement of Ernst Krause’, 29 May 1945.

9 AMA, ‘Drawing showing enemy defences, camps and roads’, 6 March 1945.

10 TNA, FCO 33/4872, ‘Exhumation and Transfer of German War Dead in the British Channel Islands’, 5 February 1962. Five out of eight Jewish graves were exhumed from the south side of the cemetery in 1961, as three had already been exhumed in 1949 for reburial in France. See TNA, FO371/100916, ‘Alderney Channel Islands, Alderney, Russian Cemetery, Foreign Workers’, 1952.

11 TNA, WO311/13, ‘Statement by OT Frontführer Johann Hoffmann’, 1 August 1945.

12 TNA, WO311/12, ‘Statement of Civ. Cyprian Lipinski’, 28 July 1945.

13 See TNA, FO371/100916, ‘Alderney Channel Islands, Alderney, Russian Cemetery, Foreign Workers’, 1952; CWGC, 7/4/2/10823, ‘Letter from Regional Inspector A/21613’, 31 May 1954; TNA, WO311/11, ‘Letter from Brigadier Shapcott to Major Haddock’, 26 May 1945.

14 CWGC, 7/4/2/10823, ‘Letter to Chief Admin Officer from SW Regional Inspector, 31 March 1955’; Ibid.

15 TNA, FO371/100916, ‘Alderney Channel Islands, Alderney, Russian Cemetery, Foreign Workers’, 1952.

16 CWGC, 7/4/2/10823, ‘A/21613. Letter from SW Regional Inspector’, 28 September 1953.

17 CWGC, 7/4/2/10823, Graves Registration Report Form, 17 January 1958.

18 For examples, see TNA, FO371/111797, ‘NS1851/3. I.W.G.C. Letter to Lord Jellicoe’, 8 July 1954; CWGC, 7/4/2/10823, ‘Letter from Len Dowsen to Wally’, 3 September 1954; CWGC, 7/4/2/10823, ‘Letter to Assistant Secretary from Chief Admin Officer’, 21 May 1956.

19 CWGC, 7/4/2/10823, Graves Registration Report Form, 17 January 1958.

20 NCAP, ACIU MF C1563, 3 October 1943.

21 The full results of the geophysical surveys undertaken in Alderney, including the GPR survey, will be published in C. Sturdy Colls, K. Colls, and W. Mitchell, ‘Non-invasive investigations at the forced and slave worker cemetery on Longy Common, Alderney’ (working title in prep).

22 The resistance survey results were first reported in C. Sturdy Colls, ‘Holocaust Archaeology: Archaeology Approaches to Landscapes of Nazi Genocide and Persecution’ (PhD dissertation, University of Birmingham, 2012), ch.5.

23 TNA, FCO 33/4872, ‘Exhumation and Transfer of German War Dead in the British Channel Islands’, 5 February 1962. Five out of eight Jewish graves were exhumed from the south side of the cemetery in 1961, as three had already been exhumed in 1949 for reburial in France. See TNA, FO371/100916, ‘Alderney Channel Islands, Alderney, Russian Cemetery, Foreign Workers’, 1952.

24 Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge, pers. comm; Although some detail was provided in 1963 concerning the graves exhumed in St Anne’s and the German Military Cemetery, the part of the letter concerning Longy Common was missing in both the CWGC and TNA files. The list of exhumations from Longy Common within the archives of Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge lists mostly unknown individuals, even though the names of the labourers were provided in lists compiled in 1945 and 1952.

25 J.F.W. Main, ‘Leave Sylt alone’, Alderney Press 27 (2017).

26 TNA, PRO HO282/21, ‘Exhumation techniques’, 2 July 1952.

27 Compare NCAP, ACIU MF C1563, 3 October 1943 with NCAP, ACIU MF C1183, 23 January 1943.

28 NCAP, ACIU MF C1978, 20 March 1944.

29 The full results of the archaeological survey, including the GPR and resistance survey, on Longy Common are included in C. Sturdy Colls, K. Colls, and W. Mitchell, ‘Non-invasive investigations at the forced and slave worker cemetery on Longy Common, Alderney’ (working title in prep).

30 The Citizen, ‘Probe into island murders: search continues on Alderney’, 18 May 1945.

Map

- Cemetery / Mass Grave

- Concentration Camp

- Forced Labour Camp

- Prison

- Worksite / Fortification