Sylt OT Camp

- Country: Alderney, The Channel Islands

- GPS: 49° 42' 17.5788 N, -2° 13' 4.1988 W,

- Address: To the south of Alderney Airport, immediately north of Vallee des Gaudulons and Val L’Emauve

- Operational: 01/08/1942 - 01/03/1943

- Labourers Imprisoned at Sylt OT Camp: Ivan Kalganov,

By Caroline Sturdy Colls and Kevin Colls

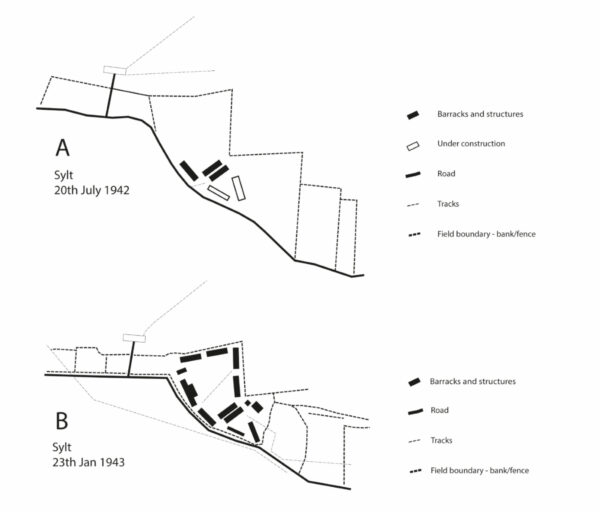

Like the other main camps on Alderney, Sylt was initially set up as a labour camp under the control of the OT. Non-invasive archaeological and archival research has confirmed that no traces of the camp existed on the 11th of May 1942 but was in operation by August of that year.1 During this early phase, the camp was small, comprising of only five buildings.2 The southern boundary of the camp was defined by an existing road. Only a simple barbed wire fence demarcated the area. Its largest group of inmates were 100-150 Spaniards, Frenchmen, women and German OT personnel.3 Around forty to fifty Eastern European workers from Russia, Ukraine and Poland were also sent there in the summer of 1942. These prisoner numbers were significantly smaller than the populations of the other island labour camps, thus making Sylt the smallest of the camps during this early period of operations. During this time, in also appears that Sylt was used as a punishment camp for labourers already on the island. At least some of the Eastern European inmates had been sent to Sylt from Helgoland and Norderney and were housed in a separate hut ‘as punishment for theft of food, loitering and similar misdemeanours’.4 The Camp Commandant was initially OT Haupttruppführer Johann Hoffmann who would go on to be the Commandant of Helgoland from January 1943. As in the other camps, Kapos helped with guarding and were ordered to treat the prisoners harshly.5

Although it has previously been assumed that Sylt was expanded in preparation for, and after, the arrival of the SS on the island, the number of buildings had in fact risen to thirteen by the end of September 1942.6 It was at this time that the camp acquired a central roll call square and the beginnings of separate compounds for prisoners and the camp administration. The expansion of the camp immediately followed the arrival of thousands of Eastern European workers to Alderney in July and August 1942 and, although most of these men were sent to Norderney and Helgoland, it seems more inmates were sent to Sylt than was recorded by British investigators after the war. In the absence of documentary evidence, the exact number of inmates in the camp remains an open question. What is known is that this general plan of the camp was then retained and expanded on when the SS arrived in March 1943. Some traces of the original labour camp structures still survive today in the area of scrubland that the site occupies, although all are covered in obstructive vegetation, and they were only made visible via the use of LiDAR technology

Treatment of inmates

Although few testimonies exist that describe life within the camp during this labour camp phase, the resources that are available paint a picture of a brutal place. During his fourteen months on Alderney Kondakov reported that, of all the camps, ‘Sylt was the most terrible’ during the OT period.7 This had a lot to do with its architecture; it was poorly built and windy due to its position on a hill, and the barracks were simple wooden buildings.8 The living conditions and its status as a punishment camp meant that amongst the general labourer population of Alderney, ‘everybody was afraid of this camp’.9 The rations in the camp consisted of coffee without milk and sugar for breakfast, thin soup (containing only small pieces of cabbage or perhaps tomato) for lunch and a loaf of bread between five men, slightly thicker soup and 20g of butter for dinner. Kalganov described how ‘it was a constant struggle to find food’ and how he was attacked by dogs owned by his overseers when he took vegetable peelings from a scrap heap at his place of work to supplement his meagre diet.10

Lipinski worked for the Sager and Wörner firm and he reported that the beatings received during this work exceeded those metered out by the OT guards and police (although they too were still very active in this regard):

‘we were beaten with everything they could lay their hands on, with sticks, spades, pick-axes. STEFAN… gave an order to cut ten sticks on which they later put rubber-tubes. Then we were beaten with them. Very often we were beaten without any reason: sometimes we were accused of laziness, but mostly we were beaten out of hatred – they called us “Communist swine, bloody Poles” a.s.o. Very often the men were beaten so long that they fell down from sheer weakness. Most of these beaten people died of wounds they had received. We were beaten every day’.11

Despite the fact that it seemingly had a lower prisoner population than the other camps on Alderney during this early period, the ill-treatment of inmates at Sylt was widespread and the mortality rate was, proportionally, very high; according to Lipinski at least one fifth of inmates reportedly perished but Kalganov’s figure suggests this it could be as high as sixty per cent. Like the other OT camps on Alderney, Sylt formed part of an indisputable landscape of violence, and in March 1943, this violence evolved – as did the camp itself – with the arrival of the SS.

References:

1 Sturdy Colls, C., Kerti, J., & Colls, K. (2020). Tormented Alderney: Archaeological investigations of the Nazi labour and concentration camp of Sylt. Antiquity, 94(374), 512-532. doi:10.15184/aqy.2019.238; TNA, WO311/13 ‘Statement by St. Feldw, Kurt Busse’, 22 May 1945; NCAP, ACIU A/756, 11 May 1942.

2 NCAP, ACIU MF C0979, 20 July 1942; NCAP, ACIU MF C1042, 23 August 1942.

3 B. Bonnard, Alderney at War 1939-49 (Stroud: The History Press, 2009), pp.138.

4 TNA, WO311/13, ‘Statement of Johann Burbach’, 28 May 1945.

5 Ibid

6 NCAP, ACIU R0827_0015, 30 September 1943; TNA, DEFE 2/1374, ‘Martin Trace’, September 1942; NCAP, ACIU C0879 5023, 23 January 1943.

7 Georgi Kondakov in Bonnard, The Island of Dread, p.50.

8 Ivan Kalganov in Bunting, The Model Occupation, p.168.

9 Georgi Kondakov in Bonnard, The Island of Dread, p.50.

10 Ivan Kalganov in Bunting, The Model Occupation, p.168.

11 Ibid.

Map

- Cemetery / Mass Grave

- Concentration Camp

- Forced Labour Camp

- Prison

- Worksite / Fortification